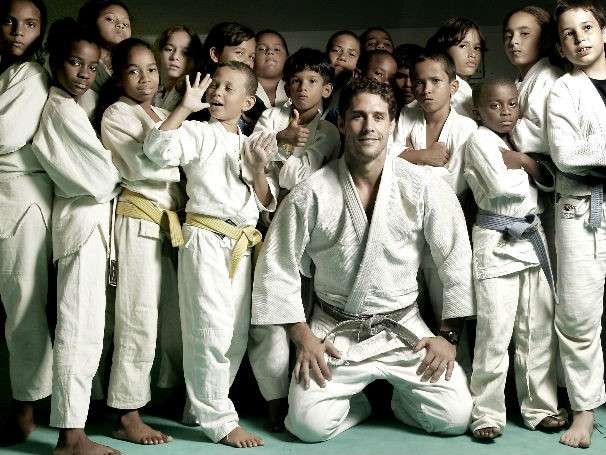

Flávio Canto is a Brazilian judoka and jiu jitsu black belt who won the bronze medal at the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens and three medals in a row at the Pan American Games.

“People who watch a judo fight usually see one guy throwing another guy,” says Flávio Canto.

“But the most important thing is to stand up.

Every time you fall, you stand up.

They are going to have to stand up a lot of times. In the end when you look back your success is determined by how many times you stood up,” the Olympic medalist nods at his students.

To stand up, no matter how many times life throws you on the ground, is what Instituto Reação, founded by Canto in 2003, is teaching the 1,200 children and youths in the ghettos of Rio de Janeiro enrolled in its programs.

The non-governmental organization promotes human development and social inclusion through sports and education, transforming underprivileged kids into “black belts” on and off the mat.

Doubts and dreams

For Canto, the battles these children living in the slums can win against all the odds of their grim surroundings are worth more than any personal sports triumphs: “In life we always seek for an activity that makes you complete.”

“Until then my life was all about judo and the Olympic dream. When the Instituto Reação came into my life I found a new way which made me feel accomplished.”

The idea to use sports as a powerful tool to change the lives of the favela kids occurred to Canto in 2000 while volunteering in a government-sponsored judo training project. In the beginning however, Canto, who himself was born to a much more privileged surrounding, was haunted by doubts.

“When this project started I began to live the reality of the slums and that shocked me a lot.

I realized that there were generations getting lost to violence, in the drug dealing war. It was common to see young boys of all ages carrying weapons very close to our academy here in Rocinha.

I still wasn’t sure if my intention of bringing sport and education (literacy) closer to these kids could work,” Flávio Canto explains.

Attending a funeral of one of his student, brutally killed by a drug gang, Canto saw one of the other students put the Instituto Reação shirt over the coffin of their friend.

“This gesture showed me the importance that our work was having and the meaning of it, in the lives of these needy people.

From that day on I stopped having doubts if the sport was that powerful, and if our socialization and education project could really make a difference.”

Making it together

All the kids and youngsters enrolled in Instituto Reação are required to participate both in judo and educational lessons six days a week all year round. The institute focuses on discipline, humility, courage and determination through judo.

Since the institute was started with funding pledged by Canto’s friends and family, it has grown to encompass four locations throughout the favelas of Rio in Cidade de Deus, Pequena Cruzada, Rocinha and Tubiacanga

Canto has been an inspiration to his students and they in turn have encouraged his pursuit to become a better athlete. In 2004 when Canto earned an Olympic bronze medal in Athens, he no longer saw it as a personal victory.

“We won an Olympic medal in Athens. They were there with me. If they didn’t exist, the medal wouldn’t exist,” he says.

Yet, for Canto, nothing beats seeing his students excel in judo and academics.

“It’s the kids who have it toughest.

They are told every day, ‘You’re not going to advance. If you are born in the favela, you’re going to die in the favela.’ And that’s an idea that we try to break,” Canto explains.

“We now have college graduates and national champions. They don’t need to just follow the destiny everyone told them they would have. They can change it. They’re the true heroes.”

From teacher to student

In the 2016 Summer Olympics, held right there in Rio, one athlete’s victory made better future seem even more within the reach for the students of the institute.

Rafaela Silva, the first Brazilian to become world champion in Judo on 8th of August, 2016, started attending classes at the Instituto Reação when she was eight-years-old. Her parents enrolled her at the institute in a desperate attempt to stop her getting into fights on the streets.

“For the children here, what Rafaela did was a very important victory,” says Michele Cunha who fund-raises for Instituto Reação.

“They see her as an example. Flavio Canto is a great model for them, of course, but he came from a more favorable background.

Rafaela could be their neighbor. They see this as a big chance for them.”

What’s more, Silva’s triumph in Rio was only possible through living up to the idea that every time you fall, you stand up. After being disqualified in semi-finals for an illegal move in London Summer Olympics in 2012, she was under racist attacks on social media. Despite the temptation to give up, she persevered.

After winning the medal, Silva’s words echoed the mission of Institution Reação:

“Judo has changed my life.

I had no dream, no goals. All I wanted was to have clean clothes.

With judo and Instituto Reação, it all changed.

I’ll leave the Olympic Village at the weekend. I’d like to go back to Cidade de Deus, be welcome as I have been and be able to give some attention to some kids and inspire them to get into sport or into a university.”

The power of meditation

Yet, despite the obvious success of his work, Canto is not one to rest on laurels. He continues to search for ways to even the odds against which the kids in the Rio’s slum struggle: “They have the right to aim higher and we try to give them the tools to get there.”

One of these tools for the past few years has been the practice of Transcendental Meditation – a well-researched meditation technique which helps kids relieve stress and achieve the inner equilibrium required to excel both inside and outside the classroom, on and off tatami.

“That was a dream come true for me because I began TM long-long time ago, I think in ’95. Things got better for me. I got the results, I won the Olympic medal. People knew me as a competitor who was always very focused.

I own that a lot to TM. But I think it is much more than just for sports. It made me a better athlete but it made me a better person and it still does for sure.”

Canto explains his enthusiasm for incorporating the practice into the life-changing activities at Instituto Reação.

“I know the power of meditating, I have experienced it for many years. And I know that they need it a lot, not only for judo, but to get better in life,” Canto adds.

The students also experience the benefits of Transcendental Meditation, both in the short and the long run.

“TM makes me feel relaxed, feel lighter, like if I could fly among the clouds. I was able to focus better on my studies, understand more about my life and reflect what I can become someday,” says a girl who attends the institute.

Black belts in life

Canto rejoices over the many academic and athletic achievements of his students. Yet he is aware that some of the success of the institute is demonstrated not by what has taken place, but by what has not happened.

“Today I know that Instituto Reação gives a sense of belonging to all of those children. I’m immensely proud of all that we have achieved.

I use to say that we want to help build black belts in life.

People with integrity and with a good sense of citizenship.

But I’m sure that our most important job is to have managed to avoid hundreds of tragic stories that could have happened to these young people and these communities, if we were not around to show them that there is another alternative, a better way to live.”

Sources: