Dr. William Stixrud, Ph.D., is a leading clinical neuropsychologist and director of Stixrud Group, a Washington, DC–based group practice specializing in the neuropsychological assessment of children, adolescents, and adults with learning, attentional, social, and/or emotional disorders. His practice in Silver Spring, Maryland, has a one-year waiting list.

To take advantage of his know-how sooner, here is a summary of some of the essential points Dr. Stixrud has made in his recent public appearances.

“For the last 30 years, I’ve worked as a clinical neuropsychologist testing kids who have learning issues or attention deficiency or autism or emotional problems – the kinds of problems that are so absurdly prevalent in young people these days.”

Data from a personnel personality inventory, which has been gathered since the 1930s, demonstrates that contemporary kids are five times more likely to have anxiety disorders or depression than young people were even at the height of the Great Depression or during WWII.

So what could have caused this epidemic of anxiety and depression?

“There are a lot of hypotheses. Some of this has to do with the incredible level of sleep deprivation that young people experience. Some people think it has to do with the increased academic pressure and competition, the fact that the kids don’t play very much. Certainly there is a lot of speculation about the effects of 24/7 use of technology.”

But while the exact reasons remain unknown, it is clear that too much stress in children contributes to development of further anxiety and depression disorders.

Perceiving danger and calming down again

So what exactly happens in the brain when we get stressed?

Dr. Stixrud explains: “The amygdala is the part of the brain which operates as a threat detection system. It is sensitive to the emotional context of experiences, to anything that’s potentially threatening like fear or anger. When the amygdala senses a threat, it will start the stress response of ‘fight-or-flight.’”

This, in itself, is a healthy survival mechanism, essential in the case of real physical danger. Yet, to prevent the amygdala from running the show too much, the prefrontal cortex – the CEO of the brain – must be strong enough to quickly regain control, assess the situation and, as the danger passes, calm the amygdala down so that stress hormone levels can return to their normal range.

“When the prefrontal cortex is not able to perform this role, it’s instead the amygdala which takes control and starts regulating the rest of the brain.”

How is the teenage brain different from the adult brain?

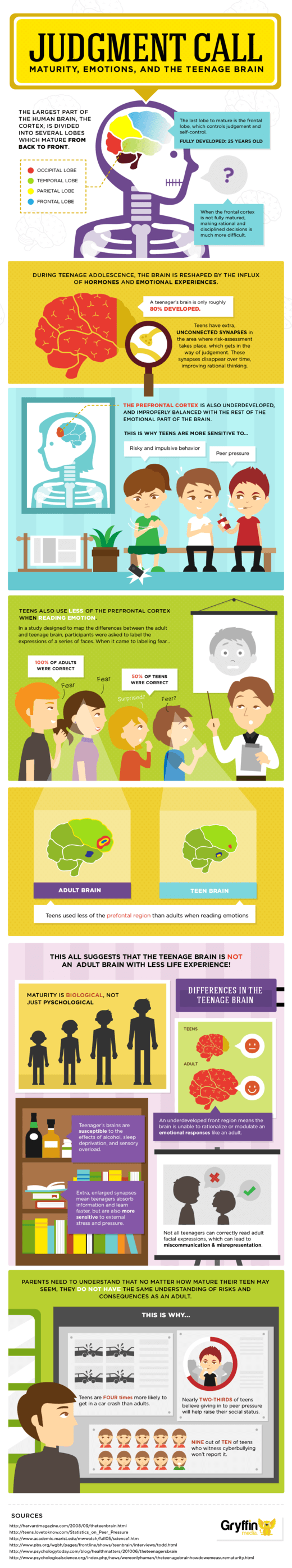

Once we understand the importance of the delicate power balance between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex, we can fully appreciate the significance of the following fact: the prefrontal cortex is very slow to mature.

“We know, for instance, that that the cognitive functions of the prefrontal cortex will not mature until 25 years of age (± 3 years), and the emotional regulation functions are not mature until a person turns 32 (± 3),” Dr. Stixrud explains.

“I lecture about the most useful stuff I’ve learned about kids’ brains, and this is the number one thing. In fact, it is so encouraging it gives people hope. People whose kids are struggling when they are 16 can be told that their children are going to have a different brain when they are 18 or 20 or 24! As the prefrontal cortex matures, it comes increasingly ‘online’ and starts to perform functions it didn’t used to do before.”

While this slow maturing of such a crucial part of our brain might sound like nature’s error in design, Dr. Stixrud assures us of quite the opposite:

“This adolescent brain is incredibly powerful, creative and adaptive. Neanderthals didn’t have adolescence; they were mature by the time they turned ten. People think that humans have an evolutionary advantage because we have adolescents who want to explore, who want to take risks, who will go out and look over the other side of the mountain.

“I heard an interview with Bob Dylan where he was asked if he could write the kind of songs that he wrote when he was 20 now. He said, ‘Are you kidding?’ Where did it come from? It came from an adolescent brain, a brain that is not fully mature.”

Optimal conditions for the developing brain

However, there is something Dr. Stixrud is worried about when it comes to these creative-adventurous minds of the young. “We know that stress affects the developing brain more than a mature brain, and stress can change the developing brain in a way that can have long-term effects.”

So Dr. Stixrud warns that the prefrontal cortex in today’s youth, given their high stress levels, might not be developing properly. Too much stress is also a big deal because of how it influences the ability to learn – a major task for teenagers and young adults.

“We know that when you are stressed – you have experienced it yourself – it is hard to pay attention to something other than what you are stressed about. From an evolutionary point of view it makes sense because if you are attacked by a predator it would not make much sense to focus on something else – it wouldn’t go well.

“I’ve been following people’s attempts to apply brain research on education for about forty years now. By far the most common implication is this: the optimal internal state for learning is relaxed alertness—because you have to be focused, you have to be alert, but you can’t be stressed. We know too that the optimal educational environment is characterized by high challenge/low threat.

“We are bored if we are not sufficiently challenged, but if we are threatened, our brain does not work.”

Building stress tolerance

What logically follows from this knowledge is that in order for children and youngsters to thrive, they must be equipped with methods to increase their stress tolerance.

“When I see all kinds of anxious and unhappy kids, I ask them, ‘What has anybody told you about how to prevent stress, or how to make yourself feel better when you are really stressed?’ And I don’t have one kid in a hundred who has anything useful to say.

“It is not that we want to protect kids from all manner of stress. An efficient stress response is that when there is something stressful, you want to have the peak in stress hormones, but when it is done, you want the stress hormones to normalize.”

This is why Dr. Stixrud recommends practices that help strengthen the prefrontal cortex.

“We know that part of what meditation practices do, both Transcendental Meditation and mindfulness, is increase the ability of the prefrontal cortex to regulate the amygdala.”

Taking advantage of peer pressure

There are other things that are useful to know when trying to make teenagers more stress resilient.

“The second major thing that is different about the adolescent brain is that there are changes in the brain’s reward system. What I’m talking about is deep centers in the brain that send the neurotransmitter dopamine to the rest of the brain, and dopamine you can think about as the power switch, the energy source. Dopamine is what you have in your brain when you’re excited about something, when you’re motivated about something; when you’re anticipating something cool happening you have higher levels of dopamine.

“What happens now in teenagers is that they have particularly high levels of dopamine in response to anything that is rewarding—to anything that is pleasurable. So if you have teenagers involved in a gambling situation where they can win money, they have these huge spikes in dopamine compared to adults.

“And what is most rewarding to teenagers is other teenagers. From an evolutionary point of view, teens want to spend more time with other teens, and they laugh together louder than we laugh and their life is more exciting in some ways and life is harder in other ways,” Dr. Stixrud explains.

This knowledge sheds light on why teenagers are at risk for being impulsive and for having addictions. Yet Dr. Stixrud points out that these characteristics of the teenage brain can also be turned into an advantage. One of the organizations reaping the benefits of positive peer pressure is the David Lynch Foundation, which focuses on teaching Transcendental Meditation to students in inner-city schools.

“I’m completely in favor of the David Lynch Foundation’s Quiet Time program.

The research on it is showing that when kids are meditating twice a day in school there are improvements in all kinds of important areas. Because teens are so rewarding to each other, what I am focusing now in my own work is trying to get kids in schools to meditate together: developing meditation clubs, even meditation buddies, and having schools develop study halls where kids can meditate—because teenagers typically don’t want to do stuff that other kids are not doing. That is the brilliance of these David Lynch school programs – everybody’s doing it.”

The benefits of being less stressed

“When you’re less stressed you can focus better, you can resist distraction better, and when you have this increase coherence in brain functioning, you can organize your thinking better, your sense of priorities is better, you can integrate information better, and you see a larger perspective,” says Dr. Stixrud, listing the many benefits of effective stress reduction.

Evidence also suggests that TM practice improves school performance, nonverbal intelligence and executive functions.

“In my field the executive functions, which include planning and organization, the ability to inhibit and the ability to be flexible, are considered much better predictors of how you do in life than IQ,” Dr. Stixrud points out.

“When we know about what TM can do to improve the lives of young people, I think it’s cruel not to teach it to them at least give them a chance to do it.”

Sources: